I came across Obsidian on my Mastodon timeline. Some time ago, the subject of “knowledge management” was a hot topic there. The pros and cons of various software programs were debated, and in a series of blog posts, someone explained how they use Obsidian and why. I watched a few video tutorials and decided to give it a try. I was particularly fascinated by the possibility of linking individual files to create my own private knowledge graph.

When I started at WiNoDa, it quickly became clear that I would have to build up a lot of new knowledge in a very short time and combine it with existing resources for my work. Creating the online self-study courses would require basic research on existing OER, new material would have to be developed, and old material would have to be updated… On top of that, there were many new contacts with specific expertise. It would be a challenge to keep track of my notes.

Obsidian seemed to be a good solution for this.

Obsidian is a free Markdown editor that stores all files in a single folder (vault), where they can be quickly found using a very good search function. Those who (like me) are old enough to know the benefits of a neat folder structure (and file naming) can create as many subfolders as they like – but it’s not necessary. (I use separate folders for blog posts, OER, minutes, and media/images, as well as a few from recommendations that I didn’t need yet.)

I created the basic structure following some video tutorials—e. g. I created some files for “templates” and “tags” that I find particularly useful.

I use document templates for meeting minutes and learning objectives, for example. In addition to predefined headings, they also contain metadata and can be easily assigned to any new file with a keybord shortcut.

Apropos metadata: all files can be accessed via a list of self-definable “properties” that enable a database-like query over all files in the vault. (There is also a very good “fuzzy” search function.)

My “tags” documents serve as a kind of index page by bringing together files that have something in common—people, topics, courses, or concepts. This allows me to link the names of the participants in the minutes to the respective tag documents for each person, which contain, for example, contact information or other notes that are important for my work, such as expertise—which I find to be an added value over traditional keyword indexing (which is also possible, of course).

This ability to easily link documents to each other is the most important feature for me. You simply write the name of the file to be linked in double square brackets. A pipe (|) can be used to create a different display name for the link, and “#” or “^” can be used to define the exact content to be linked, down to the heading or paragraph. If you write an “!” before the square brackets of the link, the linked file/heading/paragraph is even embedded and shown in the new document.

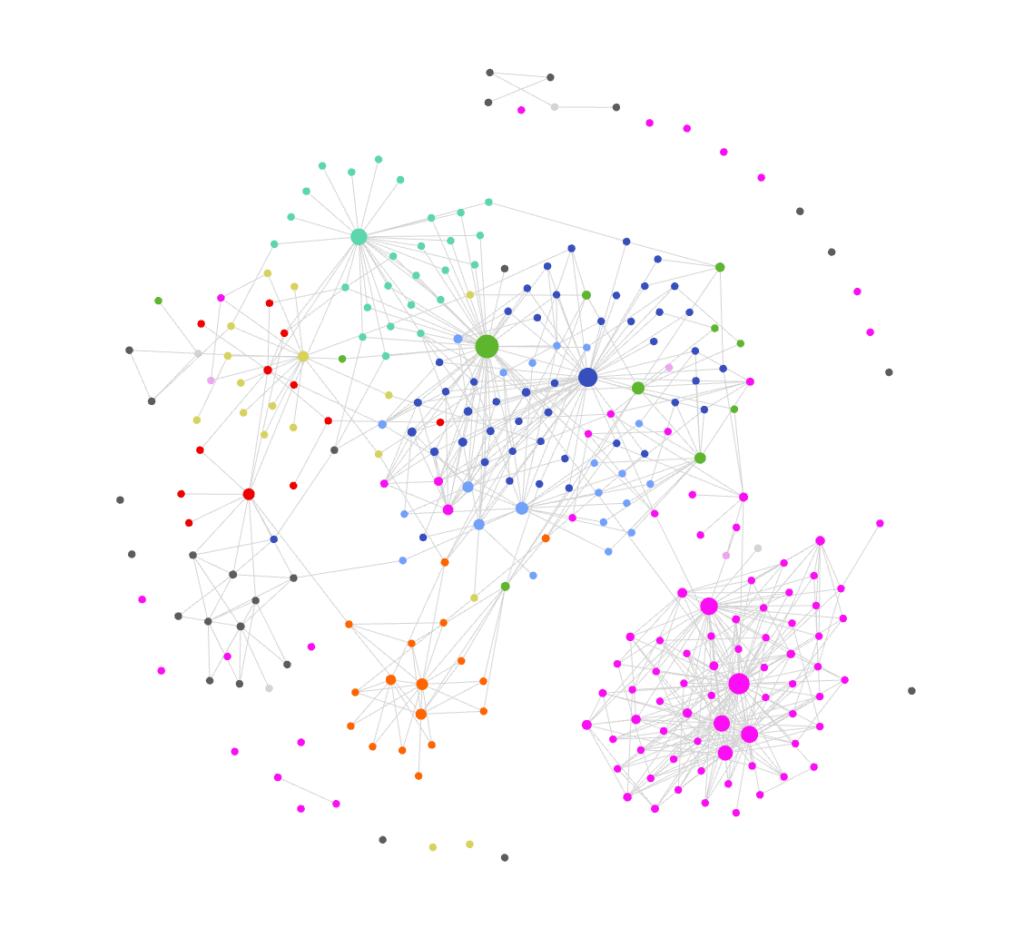

If you maintain your metadata, tags, and, above all, internal links, you will be rewarded with a personal knowledge graph. The connections between even the smallest text snippets can be displayed graphically at the file level (local graph) or across the entire vault (graph view). The nodes can be colored (using hashtags). Whether you use Obsidian as a “Zettelkasten” or for document management, unexpected or forgotten connections quickly become visible and easy to find.

For me, this internal linking of files is a real game changer—I can simply note down all the important information I come across during my research and quickly find it again using index documents, metadata, or keywords.

For example, the module plan for a course contains all the learning objectives. These are linked to the detailed scripts, which in turn are linked to the research documents, sources, graphics, or H5P. When creating the course in Moodle, I can assemble everything I need in a modular way.

Obsidian is also suitable as a presentation tool—if you open a file in the presentation view, it turns every level 1 heading (1 #) into a slide heading. Perhaps not as fancy as classic presentation tools, but sufficient in most cases (and probably much more powerful than I’ve discovered so far).

In addition, Obsidian offers numerous add-ons, created by both the developers and the community, which can be installed with just a few clicks.

Want to record and link audio files? Keep a diary? Automatic backups via Git, Zotero integration, diagram creation, task management, or mind maps…? The Obsidian community is large and continues to create new plugins. Depending on your needs, use cases, or workflows, you can put together a customized toolbox of plugins. Help is readily available in forums, tutorials, and best practice videos.

(Warning: unfortunately, some videos have a slightly unpleasant messianic undertone: the keyword “Zettelkasten” leads some people to want to dictate the “correct” use of Obsidian… And another caveat: as with any new tool, it’s worth trying it out a bit – but you can also get lost in the options. The transition to the new possibilities should be done slowly and perhaps not during a work phase with a high frequency of deadlines…)

I watched a few videos to see what had worked for others and adopted what would probably work for my workflow, too. The rest will fall into place as I use the tool and can always be adjusted if necessary. Because that’s the great thing—whenever you think, “Wouldn’t it be cool if I could count the characters per paragraph,” or visualize data, or integrate a mind map…—there’s probably already a plugin for that.

Some things, however, require a little more effort.

I actually find file export the most cumbersome. By default, Obsidian only exports to PDF format. But if I want to share meeting minutes with colleagues, for example, a Word document might be better, possibly even with a specific style. The latter can probably be done using CSS snippets (I haven’t tried it yet), but for the former, I had to install Pandoc and a plugin for different export formats.

I can then format, layout, style, and share the exported Word document as usual. This may seem like extra work, but for me it’s a bonus: layouting and formatting is/will be/remains a separate step. It’s also a small price to pay for the many advantages Obsidian offers me.

However, if you want to avoid this intermediate step, you should stick with classic text editors such as Word or Libre Office.

Please note: Obsidian is free to use, but it is not open source. Using proprietary software is never ideal, as there is always the risk that software providers will change the terms of use behind your back (even if you are willing to pay) – and then your collected files, data, photos or memories could potentially be held hostage or, worse, disappear altogether (not naming the big companies here, you know who you are).

However, the.MD file format is open source. This means that even if Obsidian no longer works, my files will always remain readable and the plain text of their links will remain traceable.

That is enough for me, for now. What about you?

Obsidian Webseite: https://obsidian.md/

Wikipedia Eintrag: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obsidian_(software)

As an academic staff at the DAI, my main responsibility for WiNoDa lies in the creation of self-study courses on discipline-specific data literacy.

Hands-on and interactive – my goal is: less technical jargon, more “aha” moments.

Because we are all working with data!